Prescription for disaster?

HE KNOCKS on the door of the suburban home. Nothing.

He waits. He knocks again, more urgently this time. Still nothing, just the happy chirping of birds in the trees.

The door is unlocked and he enters the house. “Mum, mum?” Just silence. Something is not right.

As he cautiously opens the lounge room door his blood turns cold as he sees his 80 year old mother’s body on the floor. Gripped by panic he rushes to lift her head – she is still breathing. Thank God! He calls an ambulance.

As he told us this story years later, the young man’s voice still quivered, and his eyes filled with tears, and it was clear that this event had affected him deeply.

After being rushed to hospital and undergoing an emergency blood transfusion his mother survived.

“What would have happened if I hadn’t checked on her that morning? What if I’d just gone to work like every other day?” he asks himself.

The cause of the mother’s near death experience was an overdose of a drug called warfarin, which is the active ingredient in rat poison, and was prescribed by her doctor. Warfarin is used to thin the blood, thereby reducing the risk of clots which could cause strokes. It kills rats by causing them to haemorrhage internally, and this is what almost happened to the mother. Warfarin is extensively prescribed to the elderly.

Hearing about this incident led us to wonder how often overdoses of prescription drugs occur. In an attempt to answer this question, we submitted a Freedom of Information request to ACT Health, which was worded as follows:

We are investigating accidental prescription drug overdoses (especially in the elderly) that result in hospital admissions. Could you provide us with figures (or relevant documents) on the numbers of such admissions (broken down by age) over the last five years?

Declan Kane and Phil Ghirardello from ACT Health responded to this request within just one week, and provided an extract from a vast database known as the “Admitted Patient Data Set”. The extract grouped drugs according to the World Health Organisation’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD), and ages according to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare groupings.

The extract showed that over the past five years, almost 2,000 people were admitted to Canberra’s two public hospitals as a result of poisoning by prescription drugs.

Canberra public hospital admissions due to prescription drug overdoses: 2006/07 to 2009/10

ICD Category and description Cases

T43: Poisoning by psychotropic drugs, not elsewhere classified 549

T39: Poisoning by nonopioid analgesics, antipyretics and antirheumatics 493

T42: Poisoning by antiepileptic, sedative-hypnotic and antiparkinsonism drugs 456

T40: Poisoning by narcotics and psychodysleptics (hallucinogens) 215

Total of all other ICD categories 130

Total: 1843

The table shows the top five categories, which account for 93% of all cases.

Dr Graeme Moller, a practicing Canberra physician and chair of clinical skills at the ANU Medical School, assisted with the interpretation of results.

The top category is a “catch all” that is used when it is uncertain which drug caused the condition, and is often ticked by default.

The second highest category includes paracetamol and aspirin, and the drugs used to treat rheumatoid arthritis, which are common among elderly patients.

The third highest category includes drugs to combat the debilitating tremors of Parkinson’s disease, which typically affects people over age 50.

Unlike the other categories, the fourth highest may include deliberate drug abuse, rather than accidental overdosing.

“Without going back to the individual medical records, which are protected by patient privacy, it wouldn’t be possible to say how much in this category was accidental,” Dr Moller explains.

Given that the overall figures suggest there is a significant amount of accidental overdosing taking place, we contacted pharmacies to understand the process. Pharmacist Jason Natik said that while there were potential problems in filling prescriptions, ranging from a doctor’s handwriting being hard to decipher, to typos in computer printed scripts, the pharmacist was the “last line of defence” and would check with the doctor if there were any doubts.

“Also, with the new e-script system, we’re eliminating another potential source of error because the information the doctor has typed onto the script is transferred to us electronically, removing the need for error-prone re-keying.”

Pharmacist Martyanto Rustandi said generic brands can cause overdose problems for the elderly, because patients can end up with different brand names of the same drug, purchased from different pharmacies at different times, and assume they are different drugs and that they have to take them all.

“There are moves afoot to label bottles with the active ingredient in big letters and the brand name in small letters, to avoid this confusion,” he said.

What information is given to patients to help them take their medicine correctly?

A Consumer Medicines Information (CMI) fact sheet has to be given to people on the first occasion when they collect a prescription.

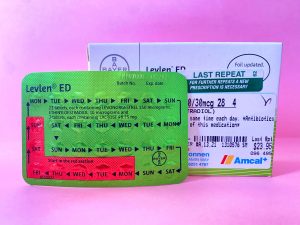

We obtained the CMI for warfarin, along with several others, to see how accessible they would be for the elderly. Unfortunately, the print was tiny, and the documents were quite technical, up to six pages long, and often buried crucial information in the middle.

The industry says it is working towards improvement.

Looking further back at the process, apart from typographical errors, there may be instances where prescriptions may not be appropriate for patients, despite the best interests of the physician.

This experience may be most prevalent in seniors, because they are often on multiple medications and may suffer from more than one chronic medical condition. As elderly bodily processes can be more sensitive to a drug’s effects, the wrong mix of medication can lead to symptoms which are then misinterpreted as a new medical condition.

This has been referred to as a “prescribing cascade”, in which additional drugs are prescribed to treat the new “condition”. The patient is now placed at further risk of developing added adverse effects relating to this unnecessary treatment, and the potential is there for this downward cycle to continue with the next diagnosis.

A doctor who requested anonymity said: “It’s concerning at any age, but with elderly physiology, under or overprescribing will have a real impact on their body’s resources for dealing with it.

“Many elderly patients suffer multiple conditions, so it’s hard to keep track of every treatment started, and what may have been appropriate for somebody when they were put on a particular drug may not be now, as conditions do resolve.”

Also, no single record of medications may exist, because they may have been prescribed by several physicians working in different locations over an extended period. While this situation may be improved by the Personally Controlled Electronic Health Record system currently being developed by the government’s National E-Health Transition Authority, no centralised system is currently available.

The statistics provided by ACT Health only capture cases that resulted in hospital admissions and do not shed light on instances where people may have received treatment outside hospital, foregone treatment entirely, or perhaps even died as a result of prescription drug overdoses.

If this was occurring, it may not be noticed, because most deaths among the elderly are attributed to old age, and are only given the most cursory examination, according to a source from ACT Policing.

“It’s a fairly straightforward procedure, and unless there’s something obviously suspicious about the death, only limited enquires will occur,” said the source. “This usually involves speaking with family members to ascertain the elderly person’s general health prior to death and obtaining a medical background report from the deceased’s doctor.”

Once police have gathered this information, it is passed to the coroner who decides if further investigation is warranted.

“If the coroner is satisfied that the cause of death is a result of an age-related illness, there is no requirement for a full autopsy or toxicology report,” said the source.

Because of this situation, deaths resulting from a prescribing cascade or any other over or under prescribing of medication have the potential to go undetected, thereby obscuring the true extent of the problem.

In the case of the mother’s overdose described at the start of this story, it appears that multiple dosages had been prescribed simultaneously, at the 1 mg, 2 mg and 5 mg level, with the intention of directing her to vary the dose on a monthly basis.

Being elderly, she misunderstood the intention and between monthly checkups consumed one tablet from each level, resulting in a life-threatening 8 mg daily dose. Without family present she may well have ended up as an “age related death”.

With our ageing population, it is imperative that systems are fine-tuned and that new safeguards are put in place to reduce the risk of accidental drug overdoses. Because no system is perfect, it is also important that, where possible, family members keep an eye on medicine use among the elderly.

Be the first to comment!