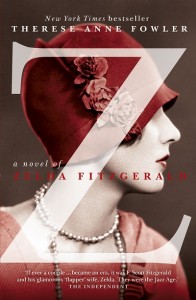

'A Novel of Zelda Fitzgerald' and the Moral Dilemma of Historic Fiction

Who doesn’t want to know what it’s like to be a celebrity? For years now reality TV has given us a glimpse into their homes, but books offer a unique opportunity to get into their heads. Or pretend to, anyway—as is the case in Therese Anne Fowler’s fictionalised autobiography Z: A Novel of Zelda Fitzgerald.

Written as though it’s the personal recount of Zelda Fitzgerald’s—wife of novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald—life, Z follows her from courtship to marriage, to being a celebrity “flapper”, to the disintegration of her health and growing frustration at living in her husband’s shadow. It’s a melancholy and intimate study of the famous historical figure.

The question the reader has to ask though: is it alright to use a real woman’s tragic life as basis for a novel?

This is the moral dilemma that comes with any historical fiction, doubly so in this case as Fowler is writing in the first person and taking on Zelda’s persona, offering her version of Zelda’s inner thoughts.

Is it biased? It would be hard for it not to be, so firmly rooted is the narrative in Zelda’s head and heart. Not to say that she doesn’t deserve our sympathy in real life, but the novel makes her an inescapably sympathetic, tragic heroine.

In the same vein, I would certainly not recommend Z to any die-hard fans of Ernest Hemingway, because Fowler effectively makes him the villain for a large portion of the book. In the afterword, the author admits to making up a particular nasty Hemingway scene, answering the question of why he and Zelda disliked each other with her own theory.

Speculation is a natural part of the study of history, but the convenient scrapbooking of historical events and imaginary ones walks a fine line between artistic license and toying with the truth to suit a purpose—in this case, the story needing a defined antagonist to embody Zelda’s personal struggle.

Is it accurate? Simply because Fowler couldn’t have been there, there are some scenes that must be fabrications. The whole thing is one person’s (naturally biased) interpretation of past events and cannot be relied on absolutely.

That being said, the book is clearly lovingly researched, and as Fowler had access to personal letters written by both Zelda and Scott, we can only assume she has a solid grasp of their ‘character’. The amount of detail is quite stunning—any reader who doesn’t know at least a little bit about the era and the Fitzgeralds runs the risk of getting lost in all the historical allusions.

Is it still a good read? If you think of Z as an intriguing, sad, lushly written story about a woman who falls in love with a writer and gets swept up in the madness and glitter of the 1920s, and not as a factual account of Zelda Fitzgerald’s thoughts and feelings, you’re likely to really enjoy yourself.

Be the first to comment!